Art, the Hungryalists, and the Beats

By Juliet Reynolds

As both movements were predominated by

poets and writers, there can be few to argue with the established

perception that the Beat Generation and the Hungry Generation were

primarily literary in character. While the two movements have tended to

invite comparison with the Dadaists, no-one would define either as an

‘art movement’, as Dada so patently was, its literary associations

notwithstanding.

Yet a closer look at the history and

legacy of the Beats and the Hungryalists reveals beyond doubt that

visual art and artists occupied a more pivotal place in their movements

than is generally supposed. This seems at first reckoning to be truer of

the Beat movement, whose annals contain a riveting art narrative that

runs from their very beginnings and has barely come to a stop. Of

course, it must be borne in mind that Beatdom is much better documented

and appraised than Hungryalism, thanks in the main to the First

World-Third World divide. While the Beats’ counter-culture evolved in

the most powerful nation on earth, the Hungryalists’ took shape in an

impoverished, underdeveloped country, that too in a single state or

region.

Moreover, Hungryalism was politically

suppressed in a way and to an extent that Beatdom was not. Ginsberg,

Kerouac, Ferlinghetti, Corso, Burroughs and the rest could turn their

notoriety to advantage, even if they didn’t desire it. This would allow

their movement to endure and evolve so that it would live on in the

collective consciousness and become a cult.

On the other hand, the movement launched

in 1961 by Malay Roychoudhury, Shakti Chattopadhyay, Samir Roychoudhury

and Debi Roy was decimated within a few years due to official hounding

as well as internal strife, a good deal of it fomented precisely because

of the harassment. The prosecution of Malay and others for obscenity

and his subsequent imprisonment was but part of the Bengal

administration’s crackdown on Hungryalism. Booked for conspiracy, every

member of the group was subjected to ruthless police raids resulting in

the confiscation of their intellectual and personal property, including

books, writings and letters. The Hungryalist artists – Anil Karanjai,

Karunanidhan (Karuna) Mukhopadhyay, and others attached to their studio

in Banaras, named the Devil’s Workshop – witnessed the seizure of their

art works and all

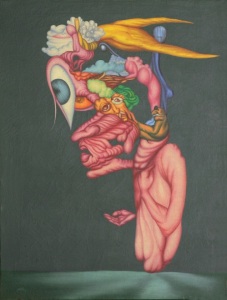

Anil Karanjai, The Dreamer, 1969

records of the movement, never to see

their restitution. Fortunately, a body of Anil’s work, created in the

immediate post-Hungryalist era, remained in his hands or became part of

collections, and because the imagery this encompasses is strongly marked

by the ideas and concerns of the movement, it provides the basis for a

more comprehensive understanding of Hungryalism. It’s not a cliché to

state that images so often speak more eloquently than words.

Just as Anil Karanjai (1940-2001) was the only adherent of the Hungry Generation to dedicate his life to art,

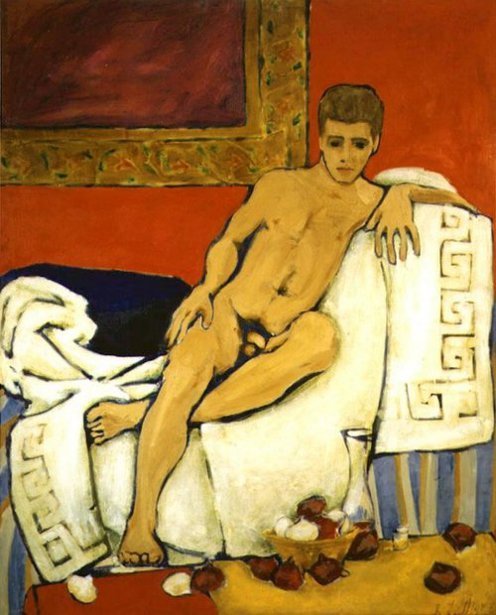

Portrait of Allen Ginsberg by Robert LaVigne, c. mid-1950s

there was a sole true Beat painter,

Robert LaVigne (1928-2014). As recorded by Allen Ginsberg, LaVigne had

helped give birth to the Beat Generation. The artist’s roomy house in

San Francisco was a gathering place for the wild, unclothed ‘bohemians’

of all genders who personified the movement. LaVigne did graphics and

poster art for the group, as well as producing his own paintings. Anil

and Karuna worked similarly with the Hungryalists.

Ginsberg and LaVigne shared aesthetic

concerns. They both focused on themes of decay and death reflecting the

angst of the young generation in the Atomic Age which, to quote LaVigne,

‘gave the lie to permanence’. The question of

creating durable art in a world with no future had a paralysing effect

on him, a state he might not have come out of had he not discovered

Beatdom. ‘The mad, naked poet’, as Ginsberg was known, and ‘the naked,

great painter’, as Ginsberg

Sketch of a Young Girl, Anil Karanjai 1991

described LaVigne, both created telling

portraits of friends and intimates, the former searingly in ‘Howl’, the

latter more gently in lines and colour. His oil portrait of the young

Ginsberg illustrates this amply.

In contrast to his Beat counterpart, Anil

Karanjai came to portraiture quite late in his life. Stylistically, the

two artists are at variance but in several of their portraits there is a

similar expression of tenderness for the subject. This is much in

evidence, for instance, in Anil’s charcoal sketch of Karuna’s young

daughter, a girl Anil had known since birth and who had been almost a

mascot for the Hungryalist artists.

Portrait of Peter Orlovsky by Robert LaVigne, c. mid-1950s

Ginsberg’s favourite work by his painter

friend LaVigne, also his rival in love, was a huge portrait of the young

Peter Orlovsky. Naked with an uncircumcised penis and crop of dark

pubic hair, the work is sexually charged but it is also sad and

contemplative. Ginsberg wrote that when he first saw the portrait,

before ever meeting the subject, he ‘looked in its eyes and was shocked

by love’. By the standards of the day, Ginsberg and LaVigne were both

pornographers. But unlike the poet, the painter managed to evade

prosecution, a remarkable feat given that full-frontal nudity was deemed

obscene until the early 1970s and homosexuality was a cognizable

offence.

Like Robert LaVigne, Anil Karanjai

painted nudes, without legal repercussions. But, as may be remarked in

his romantic canvas ‘Clouds in the Moonlight’ (1970), the Hungryalist

was more of a visionary than the Beat painter.

Anil Karanjai, Clouds in the Moonlight, 1970

The grand poet and co-founder of City

Lights, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, who was charged with obscenity for

publishing ‘Howl’ and who published the Hungryalists when they were

standing trial, was also a painter of considerable accomplishment.

Ferlinghetti’s expressionistic imagery – the earliest semi-abstract, the

later figurative and often directly political – is very compelling and

underlines his deep commitment as an activist.

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Against the Chalk Cliffs, 1952-7

The prosecuted author of ‘Naked Lunch’,

William Burroughs, is a further major figure of the Beat Generation to

have been a visual artist. But the paintings and sculptures of Burroughs

are literal horrors. He was known at times to have painted with his

eyes shut in order to explore his psyche, which was considerably

deranged, not just by an overload of hard drugs and perverse sexual

drives. Some of his canvases are riddled with bullet holes, a reminder

to his viewers that he shot his wife to death while playing William

Tell, mistaking her head for a highball. Later known as ‘the father of

Punk’, Burroughs enjoyed a friendship with the ‘father of Pop Art’, Andy

Warhol, himself no stranger to guns, even if as victim rather than

shooter. Burroughs was a frequent visitor to Warhol’s New York studio,

known as ‘The Factory’.

In their earlier days, the Beats were

loosely linked to the Abstract Expressionist painters and although the

latter were not quite so flagrant in their unorthodox personal lives,

they shocked the media and public in equal measure when it came to their

work. They also created in a similar vein, eschewing conventional art

forms and expressing themselves spontaneously; to achieve this end, they

applied rapid, fluid strokes on outsized

Anil Karanjai, Summer Morning (detail) 1971

canvases; this was consistent with ‘the

orgasmic flow’ that was a lynchpin of Hungryalism. Abstract

expressionist paintings may appear anarchic but, in common with the

writings of both the Beats and the Hungryalists, their art was

conceptual in construct; in essence, their chaos was planned.

The image of the artist creating in a

frenzy of uncontrolled passion is but a cliché, and few painters

underlined this more cogently than Anil Karanjai. Even as a neophyte,

full of fury and restless energy, he produced painstaking, considered

work. If anything, his experience with the Hungryalists, among whom he

was one of the

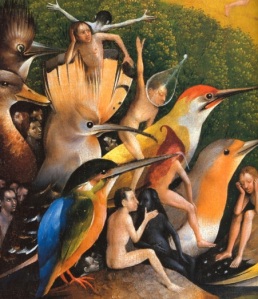

Hieronymus Bosch The Garden of Earthly Delights (detail) late 15th-early 16th century

youngest, served to heighten these

qualities. The only western painter to have influenced him in any way

was the Dutch master, Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516). Bosch’s grotesque

satirical imagery inspired Anil as he struggled to create his own

unique vision of the hierarchical, oppressive society around him.

Abstract Expressionism was unknown to Anil until much later on.

The most notorious Abstract

Expressionist, Jackson Pollock – ‘Jack the Dripper’ – likewise an

‘action painter’, is one of several artists who finds a place among the

writers at The American Museum of Beat Art (AMBA) in California. So too

is the supreme Dadaist, Marcel Duchamp, who had coined the term

‘anti-art’ before any of the Beats were born and was, therefore, one of

their idols. But the story goes that when Allen Ginsberg and Gregory

Corso met Duchamp in Paris in the late 1950s, they were so inebriated

that the former kissed his knees while the latter cut off his tie; by

now an elder of the art world, Duchamp was probably not amused. The

Beats’ conduct in those days could be so selfishly outrageous that they

managed to antagonise many, including Jean Genet, hardly known for model

behaviour himself.

It’s doubtful whether the subject of art

arose in a meaningful way between Anil Karanjai and Allen Ginsberg when

they spent time together in Banaras. The American had his mind on

‘higher things’, namely sadhus, burning ghats, mantras and ganja. Apart

from introducing Ginsberg to the harmonium, in the company of the

Buddhist, Hindi poet, Nagarjuna, Anil and Karuna taught Ginsberg and

Orlovsky the art of chillum-smoking, an almost ritualistic activity, not

at all easy to master. Otherwise, Ginsberg appears to have shown little

curiosity about the art of the Hungryalists. This did not offend Anil

who was then very young, thrilled to have the opportunity to converse in

English, a language with which he was not then familiar. Neither Anil

nor Karuna would have been overawed by the feted American, but Anil

would sometimes quote him later: “America when will you send your eggs

to India?”, from the poem America, was a favourite line.

Ginsberg no doubt was not a racist, not

at least on a conscious level. But there was an element of white man’s

arrogance within him, as there surely was in other Beats. Despite being

an anti-establishment movement, it was at some levels a highly elitist

one as well. Burroughs, for example, seems to have got away with his

wife’s killing because he was a Harvard alumnus and came from a rich

family. The background of Ginsberg was not quite so privileged but he

rose to superstardom young. No amount of ‘slumming-it’ in India could

change that, could knock him from his pedestal; in addition, he must

have been treated to a fair share of ‘chamchagiri’ during his travels.

Probably the Hungryalists were among the few to exchange ideas with him

as equals, and his failure to acknowledge their impact on his poetry and

thinking reflects poorly upon him.

Ginsberg, who was evidently quite taken

by religion in India, may not have entirely appreciated the

Hungryalists’ views on the subject. They denounced god and all forms of

belief and worship in the most condemnatory of terms. Anil’s upbringing

in Banaras had rendered him particularly irreligious; he’d been

challenging temple elders since the age of 12, often defeating them with

his superior knowledge of the Hindu scriptures and his sharp tongue.

With a scientific bent of mind, he would remain a staunch atheist

throughout his life. Early Buddhism did appeal to him, but he was

critical of the Tibetan form of Buddhism, later embraced by Allen

Ginsberg. Of course, the Beat poet’s anti-war politics and activism did

accord with Anil’s worldview, as it must have with others of the

erstwhile Hungry Generation.

As far as the Hungryalists’ politics was

concerned, Anil was at one with their ferocious attack on the entrenched

establishment, but he rejected their anarchism, their precept that

existence is ‘pre-political’ and that all political ideologies should be

precluded. He had enrolled in and quit the Communist Party much prior

to joining Hungry Generation, but he would thereafter remain committed

to the far left. It is a myth he became a Naxalite when Hungryalism

fizzled out.

There is truth in the legend that the

Hungryalists engaged in sexual anarchy in Banaras and Kathmandu, but

compared to the shenanigans of the Beats this was really quite tame.

Anil and Karuna did live with seekers and hippies in an international

commune, and indeed Karuna was its manager and sometimes head cook.

Further, a large part of their subversive activities did involve the

consumption of consciousness expanding substances including LSD, magic

mushrooms and the like, but their experiments were always undertaken in a

controlled environment. This did make a great mark on Anil but because

he never consumed substances irresponsibly, the outcome was positive,

helping to liberate and enhance his vision as a painter. This hardly

constituted ‘drug abuse’ as claimed by some.

Further, the deliberate burning of

paintings by their Hungryalist creators is a much exaggerated story,

largely based on the aftermath of an exhibition in 1967 at a well-known

Kathmandu gallery. The event coincided with a writers’ conference that

was attended by Malay and others who had remained loyal to Hungryalism.

It was Karuna alone who destroyed his work. Anil enjoyed the spectacle

but remained on the side-lines. Such anti-art gestures didn’t fit his

philosophy. His iconoclasm was of another kind.

Anil Karanjai, The Competition, 1968

Yet, whatever his divergences with

Hungryalist ideology, Anil shared the movement’s aesthetic concerns.

This is most immediately perceptible in his works of the late ’60s such

as ‘The Competition’. Painted in 52 straight hours in the Banaras

commune, the work is based on a banyan tree, a metaphor for the chaos

and struggle of the times. It also reflects the aspiration of the

Hungryalists, as well as that of the Beats, to reintegrate humans with

the natural world, a world in which obscenity is non-existent and lost

innocence is restored.

Although Anil’s work metamorphosed and

matured in his post-Hungry Generation decades, his experience with the

movement remained in his consciousness. His ideas may have come from

many sources, but he never lost sight of that Hungryalist goal. Much of

his late work is apparently classical, an expression of realism. His

landscapes in particular seem to be the antithesis of his early

‘surreal’ imagery and this tends to confound his viewers. But while it

is certainly true that the provocative, rhetorical imagery has vanished,

the foundations remain the same. From beginning to end, Anil’s art

expresses the drama of the human condition through the moods and forms

of nature. And this does accord with Hungryalist poetry. Take, for

instance, the lines of Shakti Chattopadhyay:

“Like a football the moon is poised over the hill

Waiting for the late night game and the war cries

At these moments you can visit the forest…”

Waiting for the late night game and the war cries

At these moments you can visit the forest…”

(Translated by Arunava Sinha)

Anil Karanjai, Moonrise, 1990

The poet conjures up an image very close

in mood and feeling to a late work of Anil’s, part of a series of

mysterious night landscapes. Binoy Majumdar also approaches the spirit

of this image when he says:

“all trees and flowering plants stand on their own

grounds at a distance forever

dreaming of breathtaking union.”

grounds at a distance forever

dreaming of breathtaking union.”

(Translated by Aryanil Mukherjee )

The concept of nature’s creations ‘dreaming of breathtaking union’ is echoed time and again in the life’s work of Anil Karanjai.

So too is the theme of the lonely creator

or thinker which he expressed with great range. In a canvas of 1969,

titled ‘The Dreamer’, the thinker is

Anil Karanjai, The Builder (watercolour), 1979

shaped by confrontational Hungryalism and

LSD, while a work in watercolour presents the theme in a way that

parallels a declaration of Malay Roychoudhury: “…for me, the first poet

was that Zinjanthropus who lifted a stone millions of years ago and made

it into a weapon.” Later, Anil’s solitary poets or philosophers, set in

stone, are encircled by nature, their only weapons their knowledge and

experience. All these works are executed with mastery. It reflects well

on Hungryalism that it is associated with an artist of such calibre and

originality.

…

Anil Karanjai, Solace in Solitude, 2000

…

*All the works by Anil Karanjai

accompanying this piece belong to the collection of the writer, with the

exception of ‘The Dreamer’, which is in the collection of Anjana Batra,

New Delhi; ‘Clouds in the Moonlight’ is part of the collection of The

Kumar Gallery, New Delhi and New York.

…

Bio:

Juliet Reynolds is a critic and writer, specialising in Indian art and socio-cultural issues. Of mixed Irish-English descent, she was born in Ireland and educated in England, France and Italy. A gold medallist from the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, she worked for many years as an English and drama teacher with students of diverse ethnicity. Based in New Delhi and Dehradun, she has spent most of her working life in India. Here she has established a reputation as a resolute critic and commentator, and as a bridge between scholars and the lay reader. The publications to which she has contributed include The Spectator, The Insight Guide to India, The India International Centre Quarterly Review, The Pioneer and Biblio. She is the author of In the Eyes of a Rasika: a connoisseur’s view of art and politics, art and science (Srishti/Bluejay, 2003) and Finding Neema, (Hachette, 2013). Her late husband was the Hungryalist artist, Anil Karanjai.

Juliet Reynolds is a critic and writer, specialising in Indian art and socio-cultural issues. Of mixed Irish-English descent, she was born in Ireland and educated in England, France and Italy. A gold medallist from the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, she worked for many years as an English and drama teacher with students of diverse ethnicity. Based in New Delhi and Dehradun, she has spent most of her working life in India. Here she has established a reputation as a resolute critic and commentator, and as a bridge between scholars and the lay reader. The publications to which she has contributed include The Spectator, The Insight Guide to India, The India International Centre Quarterly Review, The Pioneer and Biblio. She is the author of In the Eyes of a Rasika: a connoisseur’s view of art and politics, art and science (Srishti/Bluejay, 2003) and Finding Neema, (Hachette, 2013). Her late husband was the Hungryalist artist, Anil Karanjai.

***

The Bohemian Hungry Generation assemble at Kolkata

Abani Dhar was a seaman trainee ( Khalasi ) and sold coal on the streets of Kolkata after his mother told him to leave the seaman's job and return home. He was from a Vaishnava family and his father abandoned him and his mother when he was a boy and left home with a Vaishnavite woman. His father had once come back home to reconcile when Abani Dhar was grown up, but Abani Dhar told him to leave immediately.

Debi Ray lived in a Howrah slum, in a single room with only one toilet for all twenty residents, and before he entered school worked as an errand boy for a road side tea shop ; his mother collected pumpkin seeds to be dried and sold in the market. It was this hut of Debi Roy which functioned as collection centre of manuscripts to be published in Hungry Generation bulletins. The Hungry Generation did not have an editorial office, headquarter, highcommand or polit bureau to run the show. Each and every member was free to publish his one page bulletin if he was in a position to collect money for publication. However, the main funding was done by the two Roychoudhury brothers, Samir and Malay.

Malay Roychoudhury came from a criminal locality of Patna named Imlitala, where most of the residents belonged to lower castes and were called untouchables at that time; his father had to feed twenty persons of the extended family with his meagre income from photography business. Most of the inhabitants of the Imlitala locality indulged in dacioty, thievery, pick-pocketting, selling illegal items etc. Malay was introduced to palm toddy drinking and pig-meat eating in this locality.

One of Malay's cousin brothers, Arun Roychoudhury, he came to know when Arun died in his teens, of slow-poisoning, inadvertantly by Arun's foster mother, ie. Malay's aunt, as she wanted to keep control on Arun, was purchased from a prostitute when Arun was few month's old.

Subimal Basak's father had to commit suicide drinking nitric acid as he was in deep debt leaving his widow and children to fend for themselves. Subimal had to do menial work to eke out a living.

Subhash Ghose, Saileshwar Ghose, Basudeb Dasgupta, Pradip Choudhuri, Subo Acharya all came from uprooted refugee families of East Pakistan. They were all first generation literate. Literature was their way of fighting with the unjust inhuman society.

Kolkata or Calcutta of 1960s were not a peaceful place for young poets in their twenties to come together with a purpose. There were political turmoil and refugees from East Pakistan had been arriving constantly in search of peace and shelter. These young boys were very much disturbed and formed a literary and cultural movement which had political overtones.

About thirty poets, writers and artists under the leadership of Malay Roychoudhury accidentally met each other and started a rebellion in post-colonial post-modern Bengali literature. Since they were from lower middle class or refugee background, they were not much bothered about their overnight roof and regular food or for that matter regular bath and change of clothes. However, after the Kolkata Police filed FIR in September 1964 against eleven Hungry Generation members, many left the movement in a huff.

From the letter of Allen Ginsberg to Abu Sayeed Ayyub, it is now known that Police had interrogated twenty six poets and writers, and ultimately filed a case against only Malay Roychoudhury for his poem "Stark Electric Jesus". Malay was jailed for a month for this poem but the Kolkata High Court exonerated him after a protracted and expensive legal battle. Octavio Paz had met Malay at Patna and Ernesto Cardenal had met him at Mumbai.

From the memoirs of Hungry Generation writers we learn that some of them continued with the same shirt and trousers for months together without changing them as they did not have alternative set of dresses. They visited railway stations, especially Sealdah station, and used the toilets of trains which had just arrived or which was yet to start.

During the night they stayed at a Marwari businessman's office at Kolkata's business district Burrah Bazar, to sleep on the floor mattress which were meant for the outstation customers of the businessman.

For food they had to pool their resources together and eat at the shady stinky restaurants called Pice Hotels, mainly at Shyambazar or at College Street Market where each item was served separately and was quite cheaper.

In the evening they would visit the infamous Country Liquor Den named Khalasitola frequented by seamen and poor labourers. Here they would celebrate the birthday of famous poets like Jibanananda Das or release their newly published collection of poems. They also arranged poetry readings at Howrah railway station, grave of poet Michael Madhusedan Dutt, the Nimtala Ghat of burning corpses etc which in a way was rudimentary stage of Poetry Slam.

Since cannabis and hashish was not banned in 1960s, and there was a government shop just beside Khalasitola, they would purchase from the shop and walk back singing to wherever they could find their night shelter.

They generally published one-page bulletins due to paucity of funds and distributed them freely at Calcutta College Street Coffee House, Universities, newspaper offices and at College Street corners. Free distribution of their one-page writing was quite novel in Calcutta and senior writers and the press became aware of the presence of the Hungry Generation members. The press started criticizing them, published cartoons and this gave them popularity among readers. After their arrest, the then Police Commissioner of Kolkata Mr. P.K.Sen had commented that, "You people are engaged in serious literary activities or you are selling tooth powder through handbills ?"

Subimal Basak, the novelist of the bohemian group, who could draw sketches, drew explicit sketches with satirical humour undermining the deference shown by the middle class Bengali who were and are called "Bhadralok" towards those who were in power, and got them xeroxed for distribution. Subimal Basak was the first writer who wrote complete narrative of his experimental novel "Chhatamatha" in East Bengali dialect, which is now being followed by Bangladeshi writers. Subimal wrote poems as well in Bangladeshi dialect, now being followed by poets of Bangladesh after they became free of Pakistan's Urdu hegemony. Unfortunately, the Bangladeshi literary and religious establishment do not give due credit to Subimal Basak for his pioneering work.

Once in 1964 Subimal Basak and Malay Roychoudhury went to Champahati village in the invitation of a Baul named Ashok Fakir who lived with his wife in a hut. It was raining on that day. Ashok Fakir arranged for opium paste for them and after licking intermittently for a few hours they were quite high. All three of them went to the railway station and Subimal and Malay started dancing in a frenzy on the railway overbridge. The station master told Ashok Fakir to bring the duo down otherwise they could fall of the overbridge on the railway line. Both Subimal and Malay were completely drenched. Champahati at that time was a desolate village. The station master put the duo on a Kolkata train where on arrival both slept on the railway platform of Sealdah station and left in the morning after using the station toilet.

Ashok Fakir, got tagged to an American lady, left his Bengali wife and fled to USA with her. Ashok Fakir established an ashram in USA with his American paramour and had two children from her. Allen Ginsberg makes extensive reference of Ashok Fakir in his India Journals. Ashok Fakir had a plan to tag himself with Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky and get out of India. That did not succeed as Ginsberg was shadowed by the Indian police during his stay in India. Ginsberg left India alone leaving Peter Orlovsky behind.

Anil Karanjai and Karunanidhan Mukhopadhyay, who were painters prepared posters for the Hungry Generation and these were pasted on the staircase of the Calcutta College Street Coffee House and Calcutta University walls.Anil Karanjai also came from a post-partition refugee family of Rangpur in East Pakistan.

They, the Hungry Generation writers, poets and artists, would go out for what they called "happening" to villages and small towns just for enjoying themselves and rejuvenating their writing and drawing skills. They visited Bishnupur, Kalai in Tripura, Benares, Patna, Chaibasa, Dumka, Daltonganj, Barh, Bakhtiarpur, Rajgir, Murshidabad, Siliguri, Balurghat and enjoyed liquor made of Mahua which was quite strong compared to rice liquor of Khalasitola. They thought that living continuously at Kolkata will spoil them ; they hated the prevailing literary atmosphere of Kolkata which Allen Ginsberg had termed as "bourgeois".

The Hungry Generation writers had once distributed cheap paper masks wherein they had got printed the slogan "Take off Your Masks", which enraged senior writers who felt insulted. Once they also sent by post marriage invitation card wherein the slogan printed was "Fuck the Bastards of Gangshalik School of Poetry". So enraged were the academicians that Prof Abu Sayeed Ayyub complained to police and wrote a strong letter to Allen Ginsberg about the Hungry Generation poets, writers and artists who by then were being called Hungryalists.

Once they went to Hindi poet Rajkamal Chaudhary's village Mahishi during the Chhinamasata deity's celebration at the local temple where people were offering buffaloes for slaughter. Poeple were drunk with rice liquor and so were the Hungryalists who had gone there as Rajkamal Chaudhary's guests. The whole night they were in drunk frenzy with buffalo blood splattered all over their body and ate cooked buffalo meat with the villagers. Rajkamal Chaudhary died young because of bohemian excesses. Rajkamal Chaudhary's famous poem "Muktiprasang" has a reference to Malay Roychoudhury. A similar reference of Malay had been made by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra in one of his poems.

Another Hungry Generation poet who died of excesses was Falguni Roy, who used be in a stoned state due to over indulgence in cannabis and hash and could publish only one book of poems before his death. Falguni Roy's manuscripts were collected by Subhash Ghosh and Subimal Basak which were added to the first edition of his book "Nashto Atmar Television". Hungry Generation poet Utpalkumar Basu termed the publication of Falguni Roy's collection of poems as end of modernism in Bengali literature.

1n 1965 Tridib Mitra, Malay Roychoudhury and Subimal Basak visited Subo Acharya's house at Bishnupur. They had a great time, as one of them has written in his memoir, smoked pot and after visiting the terracotta temples and conch shell cutting artisans, started walking aimlessly crossing several green paddy fields when they came to the shore of a river. They took out their shirt and pant, held them on their head and crossed the river completely naked, to the surprise of the nearby cultivators. After crossing the river, they sat down beneath a banyan tree and kept on smoking pot till evening, all four of them completely naked. They recited their poems from memory. The cultivators, including women, passed by, but nobody bothered them.

Around the years 1966-1967 Basudeb Dasgupta developed a sort of Henry Miller type life in Kolkata and started visiting hookers known to him and became close to one named Baby at the 5B number house at Sonagachhi. In a letter dated 6 December 1967 to Saileshwar Ghose he laments that Baby has shifted to number 10 hooker den and the 5B house has become desolate without her. He also talks about Abani Dhar who was with him one day and gave a little money to a hooker named Meera. Abani Dhar was a late entrant to the Hungry Generation movement. Before Dhar died, Malay Roychoudhury had arranged publication of his short story collection titled "One Shot" based on his experience of insults that he faced in his life.

Abani Dhar was a trainee seaman ( khalasi ) and Basudeb Dasgupta encouraged him to write in his own illiterate diction. Basudeb Dasgupta was more attracted to Baby just as Abani Dhar was attracted to Meera. The third hooker in their life was Deepti. They were joined once in a while by Saileshwar Ghose after his wife died. Baby appears now and then in Saileshwar Ghose's poems. Unfortunately Saileshwar Ghose's wife, son-in-law and daughter died one by one and Shaileshwar Ghose also died on the operation table of a Government hospital, though he could have visited a private hospital where there were better facilities. Saileshwar was more interested in constructing his bungalow house than looking after his family members.

Baby introduced herself to the Hungry Generation poets and writers when in 1965 David Garcia, an American Hippie poet visited Kolkata and wanted to fall in love with a Bengali girl. Since it was not possible to fall in love and make love to her within a week the Hungry Generation poets and writers took David to the famous hooker's den at Kolkata. When Baby saw a foreigner, she became interested and introduced herself, ordered for country liquor for all poets and writers who became drunk after a couple of bottles. David liked her after he slept with her for an hour. Since the poets and writers did not have sufficient money Saileshwar went after David has done his love making. This was the beginning of the affair of the Hungry Generation poets and writers with Baby, Deepti and Meera, three different types of women, different voices, different body structure.

The bohemian Hungryalists Malay Roychoudhury, Sabimal Basak, Anil Karanjai, Karunanidhan Mukhopadhyay, Kanchan Kumar and Samir Roychoudhury went to Nepal without much money and stayed there for months together. They assembled at Patna residence of malay Roychoudhury, crossed the river Ganges in a boat, and from Sonepur took a train to Raxaul at Nepal border. Tridib Mitra had also arrived, but his girlfriend Alo Mitra, had a doubt about what the poets and writers were going to do at Kathmandu where cannabis, hash and Hippie women are available on call. Alo Mitra took back Tridib Mitra to Kolkata.

The Hungryalists crossed the border in a rickshaw and took a bus to Kathmandu where Karunanidhan Mukhopadhyay used his contacts with some Hippies he knew at Benares and got a room in a big thatch Palace about hundred yards in length and breadth with hundreds of one room tenements on three floors of the wooden building at an area named Thamel in Kathmandu town.They rented a single room. For bed they were provided hay stacks on which a cotton cover was spread. Kathmandu at that time was flooded with Hippie boys and girls and the building the Hungryalists stayed in were jam packed with them, American, European and even Japanese. Rent was quite cheap. Just one rupee per month per head. When the Nepal Academy of literature came to know about the arrival of the Hungry Generation writers, poets and artists, they deputed the Deputy Secretary Mr. Basu Shasi to arrange for their daily food and sight seeing as well as poetry reading at various towns in Nepal.

Hash was very cheap at Kathmandu at that time. The Hungryalists would go out in the evening in groups or alone, find a temple where old men in a circle were smoking. The Hungryalist would sit beside them as a part of the circle and get his turn to smoke, get high, and move on, or if stoned, go into the temple and wait till the effect was over. The evening gong of the temples were quite soothing, they have written.

The Hungryalists were sometimes invited for poetry readings at other centres in Nepal where arrangements were made for them to drink strong Nepali country liquor Raksi and buffalo meat cooked with hand by pressing the boneless pieces for a few hours with local masala, or deer meat pickle. Since Malay Roychoudhury's trial had become news in Nepali news papers, he had to recite his poem Stark Electric Jesus almost everywhere they went. The local newspapers published photographs of Subimal Basak, Malay Roychoudhury and Samir Roychoudhury. After the Hungryalists became known to the local poets Samir Roychoudhury collected poems from Nepali poets and brought out an anthology when he returned to India.In November 1964 TIME magazine had published the news of the arrests of Hungryalists with a group photo, which made them known to the Hippies and a few Hippie girls fell for these poets and writers. There was music, hash and love at the Thamel wooden Palace.

Karunanidhan Mukhopadhyay was able to convince the African-American owner of Max Galarie at Kathmandu to hold an exhibition of painting by himself and Anil Karanjai. It was a great success for Anil Karanjai as almost all his paintings were sold. On the last day of the exhibition the unsold paintings were heaped together and set on fire. The Hungryalists, Nepali poets and the Hippies who had gathered started singing and dancing around the fire. A couple of Hippies played guitar and flute. After the fire was extinguished Karunanidhan Mukhopadhyay gathered ashes on his palm and put black dot on everybody's forehead.

Karunanidhan Mukhopadhyay's father had abandoned him and his mother when Karunanidhan was a child and married a Burmese women. His father stayed in Burma whereas Karunanidhan returned to India with his mother and led a life of a street child, earning in whatever way he could to sustain his family. He did not learn painting at any school or academy like Anil Kranjai and learned the craft from Anil Karanjai. Karunanidhan got jobs of drawing book and magazine covers. When the Hippies started to arrive in Benares during the Vietnam war he became their guide in the city as he knew the city like the back of his palm. The Hippies were impressed and gave him expenses. A Hippie woman proposed to Karunanidhan that they select a place, build a hut and live there like Adam and Eve. The lady and Karuna lived like Adam and Eve, completely naked on the other side of Ganges river where nobody lived. Karuna would cross the river in a boat which the lady had hired and make purchases for a fortnight and go back to his lady love. Malay Roychoudhury has written that he was quite embarrassed to find them naked and dirty when Anil Karanjai took him to the couple's hutment. The couple had given up taking bath and combing hair since they settled on the shore.

Based on his experience at Kathmandu and Benares with cannabis, hash, LSD and Hippie women Malay Roychoudhury has written an experimental fiction titled "Arup Tomar Entokanta" in which explicit sexual encounters are woven into philosophical discourse. The novel had shocked the readers when it appeared for its counter cultural and anti-establishment approach in a sexually path breaking prose.

In 1964 Subimal Basak and Malay Roychoudhury visited Behrampore in Murshidabad district to get their bulletins and magazines printed at a press known to Samir Roychoudhury. They had to arrange with this press as the Calcutta presses refused to accept their manuscripts due to threats from other groups, especially the "Krittibas" group led by Sunil Gangopadhyay.

After handing over the manuscripts to the press Subimal Basak wanted to visit his maternal aunt and maternal grandmother at the village Khagra. They took a night train which was empty at that time, though now it would be impossible to get a seat in any train. The granny treated them well with good food and fish preparations. In the night Subimal Basak and Malay Roychoudhury slept on a bed made for them on the floor with mosquito net. In the morning they found a venomous snake with hood on the roof of the net, They had the bundle of Hungry Generation bulletin with them and with that bundle threw away the snake out of the net roof. Their shouts had attracted Subimal Basak's aunt and granny. They saw the snake slither into a hole beneath a tree. What the granny did was quite surprising. She took a pot of sugar and made a trail thereof from the den of red ants to the tree under which the snake had taken refuge. By afternoon it was found that the ants had almost eaten up the snake which had come out of its hole and was writhing in pain. It was just a depiction of what the Hungry Generation writers were trying to tell the Bengali middle class society, that Cultural snake has to be lured with sweetened morsels of prose and poetry and then destroyed.

Short story writer Basudeb Dasgupta, who got inclined to Marxist shenanigans of the ruling left was later disillusioned and presented his case in his novel "Kheladhula". Malay Roychoudhury had already warned him that most of the leaders of the Communist Party had demanded bifurcation of Bengal on religious basis and when the partition came, they were the first to leave East Pakistan and flee to India leaving the lower "Namahshudra" strata of Bengali society trapped in Fundamentalist nightmare. Basudeb Dasgupta gave up writing thereafter and became a regular to the three hookers named Baby, Deepti and Meera. Pradip Choudhuri once said that Basudeb Dasgupta feels defeated and has become a pervert.

Subo Acharya, was unable to bear the burden of bohemian life. Though he went to Samir Roychoudhury's Dumka house in Bihar for a change, he ultimately sought refuge in religion and became a disciple of Anukul Thakur. He did not publish any poetry collection though he wrote poems for Subhash Ghose's magazine "Khudharto" and Pradip Chopudhuri's "PHoooo."

Pradip Choudhuri had gathered some poets in Tripura and wanted to spread the Hungry Generation movement to the state. However, after Arun Banik, one of the aspirant member was murdered by political goons his efforts petered away and he concentrated on French poetry of the time and visited France, Canada, UK and America for poetry reading and talks at various Universities on Bengali Poetry. Pradip Choudhuri's poem was staged as a ballet in Paris.

Pradip Choudhuri was sent for school and college education, by his father to R.N.Tagore's Visva Bharati University from which he was rusticated because of his explicit poems in which he named a few of his female class mates. He later studied English at Jadavpur University and taught at a private school till retirement.

In North Bengal Alok Kumar Goswami and Raja Sarkar had started a Hungry Generation magazine named "Concentration Camp". Thie efforts were brought to naught by Shaileswar Ghose who thought that his importance will dwindle because of Goswami and Sarkar. The group got dismantled at the beginning itself. However, another poet named Arunesh Ghosh of the same group attracted the attention of Calcutta Literary Establishment but did not get the requisite importance for having joined the Hungry Generation movement. Arunesh Ghosh had spent most of his younger days in the vicinity of hookers den near his village and the women keep cropping into his poems very often. Arunesh Ghosh died in a pond while taking bath, though he was a good swimmer. It is conjectured that he committed suicide for having been neglected.

Samir Roychoudhury not only toured the areas of sweet water fishermen, fishnet weavers and boat-makers to understand their life and living but also spent more than a year on fish trawlers in the Arabian sea. His bohemianism has been a completely different story. He lived the life of fishermen during his experience on sea trawlers which gave him insight into the forms of short stories he was going to write later. Ashok Tanti, the critique and novelist, has compared Samir Roychoudhury's contribution to Bengali literature with the famous fiction writer Manik Bandyopadhyay.

Among all the Hungry Generation writers, poets and artists, it is Malay Roychoudhury, the founder of the movement, who gathered vast experience during his constant tour of entire country for about forty years. He based his novel "Ouras" on his experience in Abujhmarh jungle of Chhattisgarh where life of the Maoists intersect with the life and culture of the tribal people. Malay Roychoudhury toured West Bengal and Bihar and wrote his novel "Naamgandho" on the plight of poor potato growers and the politics of ruling parties and castes in controlling Cold Storage and off-season potato business. He wrote the novel "Nakhadanto" on the plight of jute farmers and the politics of jute mill owners in connivance with the ruling political class and their business interests. Most of the jute mills are being closed one by one so that the land may be used by the builder-promoter lobby. For writing "Nakhadanto" and "Naamgandho" Malay Roychoudhury did extensive research on the subjects and visited hundreds of farmer families and several party offices in the guise of an Urdu-Hindi speaking reporter ; he had to grow and maintain beards and moustache and named himself Choudhary Sahib. His post-modern novel "Arup Tomar Entokanta" reflects the anti-establishment bohemian lifestyle of the Hungry Generation writers, poets and artists of 1960s.

There are heaps of misinformation garbage being spilled out even after so many decades. Take the case of the book "The Blue Hand" written by Deborah Baker on Allen Ginsberg's life in India. Mrs Baker had no need to bring in the Hungry Generation in her book, and even if she did so she should have interviewed the members of the movement who were available at Kolkata. Instead thereof, she contacted Tarapada Roy, a member of pro-establishment "Krittibas" group for information about the Hungry Generation movement. Everyone in Kolkata knew that Tarapada Roy was the nephew of the Deputy Commissioner of Police of Kolkata Detective Department who was in charge of filing cases and issuing arrest warrants against eleven Hungry Generation writers and poets in 1964. Mr Baker has completely distorted history and denigrated the Hungry Generation movement in her book. She talks about Shakti Chattopadhyay being identified by Bonnie Crown of Asia Society for the scholarship for visit to USA, but did not explain how Sunil Gangopadhyay maneuvered everything and went himself in place of Shakti Chaatopadhyay.

The pro-establishment writers are still active against the Hungry Generation movement. In the Durga Puja issue 2016 of "Kabisammelan" poetry magazine, reporter Gautam Ghosh Dastidar has written a lengthy article demeaning the contribution of the movement, on the same lines as the newspapers Ananda Bazar Patrika, Jugantar, Darpan, Jalsa, Amrita, Chaturanga did in the 1960s, despite the facts that Ph D and M Phill dissertations on the movement have been published. A pro-establishment guy named Sabyasachi Sen continually harps against the movement in whichever magazine he is asked to contribute.

( Information for this article collected from publications available at Little Magazine Library and Research Centre, 18 Tamer Lane, Kolkata )